Founding Fathers - John Penn

John Penn

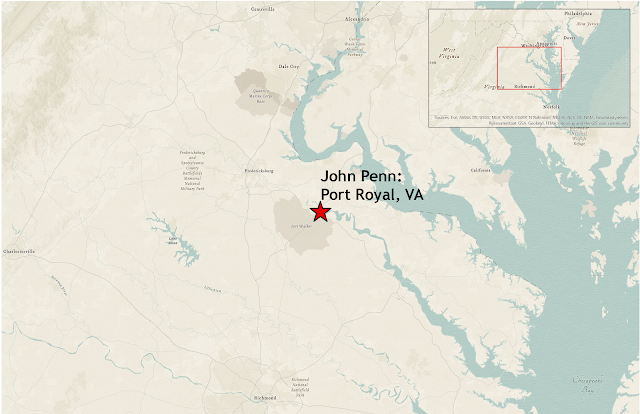

Born: May 17, 1741 (Port Royal, Virginia)

Died: September 14, 1788 (Stovall, North Carolina)

The Penn name is typically associated with the family that founded and dominated Pennsylvania's early history, but this week we'll look into the story of someone else who has been overshadowed. John Penn began his life in simple surroundings, the only son of moderately wealthy parents named Moses and Catherine Penn. Moses was a farmer who did not see the need in being educated in order to become successful, and therefore young John only received two years of schooling as a child. At the age of 18, however, John lost his father and was taken in by an uncle named Edmund Pendleton, an attorney whose friends included George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and John Adams. In Pendleton's library John found a wealth of legal education and by 1762 he was admitted to the bar and licensed to practice law. The following year he married Susannah Lyne at the age of 22, and the couple would eventually have three children.

For the following nine years John Penn was an attorney in Virginia, during which time his political leanings became increasingly revolutionary. At one point he was taken to court because of remarks he had made about the king at a public meeting about taxation which were distasteful at best, and treasonous at worst. Despite having a sympathetic judge, Penn was found guilty but punished only with a nominal fine of one penny. Standing on principle, he refused to pay. Not wanting to create conflict or embarrassment for his uncle, who was by that time a judge and still hoped for reconciliation with Britain, Penn decided it would be more respectable to move away from his mentor. As several members of the family had relocated across Virginia's southern border into North Carolina, Penn followed their lead in 1774 and took his wife and two surviving children to a new home in Granville County, between Stovall and Williamsboro, NC. He made a name for himself quickly and was elected to the colony's Provincial Congress within a year, followed by a selection to represent North Carolina at the First Continental Congress later in 1775.

Despite his popularity at home, John Penn found conflict among the established colonial leaders who at times viewed him as a outsider. One such dispute led Henry Laurens, who was the President of Congress at the time, to challenge Penn to a duel. On the agreed-upon day the two men and their seconds ate breakfast together where they had all lodged, but as they attempted to walk to their appointment through Philadelphia's muddied streets Penn offered the older Laurens assistance, which apparently cured them both of ill-will and they returned to the tavern for drinks to settle the issue without a shot being fired. Although he stated his intent to see a formal separation from Britain, Penn nevertheless supported the Olive Branch Petition to extend a last chance of reconciliation to King Charles. When it was turned down, Penn joined with his fellow delegates in casting votes for independence, signing the Declaration beneath the names of his two fellow representatives from North Carolina.

For six years John Penn served in Congress, signing the Articles of Confederation and supporting the war effort. At one point, when a pamphlet was distributed accusing certain members of corruption, Penn spoke out against the effort to charge both the writer and publisher for slander. The freedom of their speech was important, he argued, and persecuting them would only give them more credibility and power. When the British invaded North Carolina in 1780 and the governor, Abner Nash, realized he lacked sufficient emergency powers, Penn was one of three men named to a Board of War tasked with protecting the state. As the other two members were rarely present, Penn wielded unparalleled authority to affect military activity, and lavishly supported Nathanael Greene's troops and Francis Marion's militia as they battled British General Cornwallis. Penn received significant credit for his role in weakening Cornwallis prior to his eventual defeat at Yorktown, but Governor Nash's successor, Thomas Burke, convinced the legislature to have the Board of War disbanded after certain members of the military objected to civilian interference. Penn returned home, having accomplished much for both his new state and his new nation, and resumed his legal practice. He lived a quiet life for a number of years and died in 1788 at just 47 years of age.

The signature of John Penn can be found as the third signature on the third column beneath the Declaration of Independence.

Comments

Post a Comment