Founding Fathers - Charles Carroll (of Carrollton)

Charles Carroll

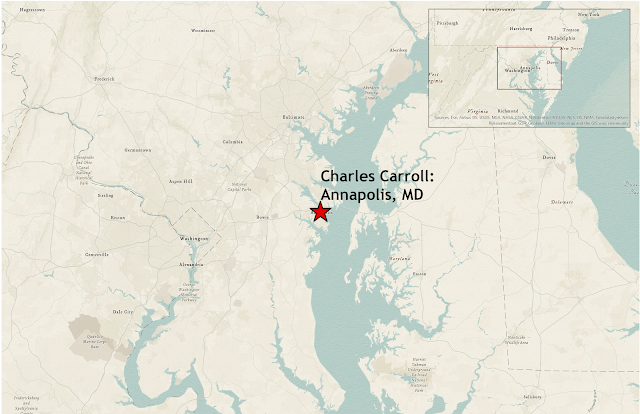

Born: September 19, 1737 (Annapolis, Maryland)

Died: November 14, 1832 (Baltimore, Maryland)

My oldest daughter recently graduated from high school and began attending college. Like many senior classes, hers took time to label each other with so-called "senior superlatives" that guessed what the student would become or identified a trait for which they were best-known. This week's focus could have been tagged with many superlatives by his peers. He was the only child of two wealthy parents, Charles Carroll of Annapolis and Elizabeth Brooke, who were not yet married due to inheritance issues. They would not, in fact, formally wed until their son was 20 years old. Although Maryland was founded by a Catholic man and an Anglican majority, and had passed a law as early as 1649 defending the free exercise of any Christian religion, by the middle of the 18th century Roman Catholics were denied the right to hold public office or practice certain professions. Young Charles Carroll was schooled for a time at home before secretly going to receive a Jesuit education on the east side of Chesapeake Bay alongside his cousin, John, who would one day become the first American Catholic Bishop. At the age of 12 the pair were sent across the Atlantic to begin an extensive European education, beginning in 1749 at the College of St. Omer in northern France and extending to Paris' Louis-le-Grand as well as several other schools across that country. By 1760 Charles had travelled to London in order to study law at Inner Temple, but was similarly restricted from practicing there due to his faith as his fellow Catholics had been in Maryland. When Charles finally returned home in 1765 he was exceptionally well-educated, with personal experiences of inequality and a passion for democratic ideals.

As the only heir to a significant estate, Charles Carroll was gifted one of his family's properties northwest of Baltimore, and he took on the name of the town to differentiate himself from his father and several others of the same name. Ironically, however, the home he built there would never be his primary residence as he remained at an estate closer to Maryland's largest city, known as Doughoregan Manor. Three years later he married his cousin, Mary Darnall, with whom he would have seven children. Having been present in London when the Stamp Act had been initially discussed, Carroll had strong opinions about the fairness of such taxation. Although restricted from holding public office or practicing law, he found a clever way to enter the political debate and shape public opinion. In a series of published articles, Carroll debated the principles of democracy, religious freedom, and exercise of conscience against the powers of appointed leadership. Signing his articles as "First Citizen", he did not remain anonymous for long and quickly became a target of Daniel Dulany, who not only disputed his conclusions but also attacked his character and faith. Carroll's arguments were so well received that many of the fees required by the British colonial government were struck down, and he quickly became a respected voice for independence. The long-standing prejudice against Catholics was finally swept aside in 1774 when Carroll was elected to the 2nd Maryland Convention, and soon thereafter Benjamin Franklin and Samuel Chase invited the French-speaking Carroll to join them on a trip to Canada to seek support for independence. Their efforts were not successful, but all three were quickly sent to Philadelphia to participate in the Second Continental Congress. Because Carroll himself was named a delegate on July 4, 1776, he was not yet present when the vote for independence was taken but "most willingly" signed the document when presented the opportunity the following month. He was arguably the richest and most educated signer, and the only Roman Catholic.

After serving on Congress' board of war for two years, Charles Carroll returned to Maryland to help form and lead a new state government. He chose to take a seat on the Maryland Senate in 1781 after turning down the opportunity to return to the Continental Congress, and he remained there until 1800. His personal life was shaken considerably in 1782, when both his father and wife died within a 10-day span. The following year he was elected President of Maryland's Senate, and when the Constitution was ratified he was selected to serve as one of Maryland's first US Senators, which he did until 1792 when the state outlawed holding simultaneous state and federal offices. Carroll retired from public life after losing a re-election bid in 1800 and returned his focus to personal and business interests. He was instrumental in funding the creation of Georgetown University, as well as serving on the founding boards of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, Chesapeake & Ohio Canal, and both the First and Second National Bank. Although he was given a large number of slaves and was said to have owned more humans than any other individual at the time of the Revolution, Carroll was personally uncomfortable with the institution of slavery and tried on occasion to have it abolished. Like many others of the time, he did not free the people who worked his land or maintained his many properties, but in the final few years of his life he became president of the American Colonization Society which attempted to solve the issue by relocating former slaves to Africa. When both Thomas Jefferson and John Adams died on the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, Charles Carroll became the last surviving signer. Six years later, in the fall of 1832, he died in his daughter's Baltimore home at the age of 95 - the oldest age of any Founding Father.

The signature of Charles Carroll of Carrollton can be found as the fifth name on the third column beneath the Declaration of Independence.

Comments

Post a Comment