Geography of War - The Battle of Tours

The Battle of Tours (Islamic Invasion of Gaul)

Date:

October, 732

Modern Location:

Western France

Combatants:

Umayyad Caliphate (led by Abd al-Rahman al-Ghafiqui) vs Francia and Aquitaine (led by Charles Martel)

Summary:

After the fall of the Roman Empire, the majority of western Europe fell into small feuding states. By the year 700 AD, a threat from external invaders had become a legitimate concern as the Umayyad dynasty had established control of lands across northern Africa and across the Middle East, forming the second Islamic caliphate after the death of Mohammed. In 711 AD, Umayyad forces crossed the Strait of Gibraltar into the Iberian Peninsula and began to conquer the Visigoth kingdom that controlled most of modern-day Spain and Portugal. It took just eight years for the Umayyad caliphate to consolidate control of the peninsula, creating the Islamic state of Al-Andalus, and turn their focus towards the Franks to the north. The invaders did not seem to take the Germanic tribes in Europe very seriously, as most of their local lords were focused on expanding their influence and did not have armies with sufficient numbers or experience to repel more seasoned forces. At the time, the Franks were not entirely unified and the bulk of power was not held by the king but instead by the mayor of the palace, who effectively controlled the kingdom's army. Charles "The Hammer" was the illegitimate son of a powerful Frankish leader named Pepin whose skill on the battlefield had given him prestige and recognition as the head of the majority of Frankish lands, and after establishing an eastern border with the neighboring Saxons the primary opposition he faced was Duke Odo the Great, who controlled the semi-autonomous region of Aquitaine to Charles' south. Although the two had several conflicts and were not on the best of terms, the invasion of the Umayyad forces forced them to set aside their differences to face the common foe. Forces under the command of Abd al-Rahman avenged a previous defeat at the hands of Odo during the siege of Toulouse by sacking the wealthy city of Bordeaux early in 732, and the duke fled north to seek help from Charles.

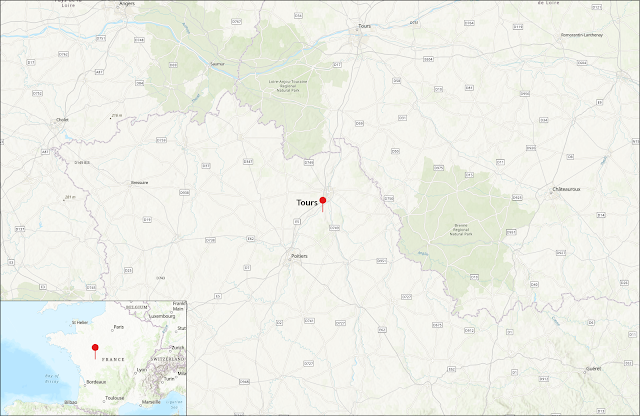

Fortunately for the Franks, the Umayyads took several months to loot Bordeaux, giving Odo and Charles time to gather their full strength and choose the best location for battle. Abd al-Rahman continued to head north towards Tours, and unexpectedly encountered a much larger force blocking his route. While the Franks had considerable knowledge of Umayyad strength and tactics, the invaders seem to have had a shocking lack of intelligence on the Franks, to the point that they apparently had no idea who Charles Martel was or how strong his experienced army was. Although the exact location between the cities of Poitiers and Tours where the Franks took their position is unknown, it is likely they were near the confluence of two rivers, the Vienne and the Clain, and they successfully hid their numbers on a hill blocked by trees as they awaited their enemy's advance. Charles' army had a strong infantry that had trained and served him for over ten years, but very few mounted forces to combat the renowned cavalry that they knew would attack. As such he refused to expose his full army to an open field of battle and instead was content to block the road with a phalanx and engage in skirmishes over the period of several days, despite the fact that the Umayyad forces continued to receive reinforcements from various raiding parties that were rejoining al-Rahman. After a week, the invading forces finally attacked with a full charge of heavy cavalry into the face of a tight, thick defensive wall presented by the defending infantry. In a rare instance, the infantry held its ground despite repeated attempts. The few mounted attackers who breached the ranks were soon met by Charles' second line. Contemporary accounts suggest that a small party of Franks led by Odo were able to go behind the Umayyad lines and attack their camp, which caused a portion of the cavalry to retreat, and during the attempt to rally his forces al-Rahman was cut down and died. The two armies separated, and during the night the Umayyad forces left their tents behind and retreated from the field.

Scene of the presumed location of Charles Martel's defensive stand:

Geography:

The wooded hill where the Franks took up defensive positions served two purposes. First, it obscured their numbers from an enemy that lacked basic understanding of who they were fighting. Second, the Umayyad cavalry that was nearly always their most powerful battlefield asset was slowed by having to ascend while maneuvering around trees. The horses were not able to simply ride through the phalanx and instead had to fight their way through the heavily-armed and well-trained wall of infantry. Additionally, Charles Martel employed a strategy to march through mountain terrain while avoiding the main travel roads to avoid being discovered by scouts. This allowed the Franks to maintain the element of surprise while depriving al-Rahman of vital information that may have allowed him to make better decisions during the battle.

Result:

News of the victory quickly spread, and Charles Martel was hailed as a savior and defender of Christian peoples against the Muslim hordes. It has been debated whether or not a victory by the Umayyad forces could have ushered in a period of Islamic dominance over western Europe, but after Tours the steady expansion of the Umayyad Caliphate stopped at the border of Al-Andalus. Charles himself continued to expand his influence, and was able to lay the foundation for his son Pepin to become the first Carolingian king of the Franks. His grandson Charlemagne would eventually build upon the successes of his father and grandfather to first become king of both the Lombards and Franks, and then ultimately establish the Holy Roman Empire which united the majority of western Europe under his control.

Comments

Post a Comment